Thursday, April 24, 2025

Friday, April 11, 2025

Fibber McGee and Molly in Hollywood-1937

Monday, April 07, 2025

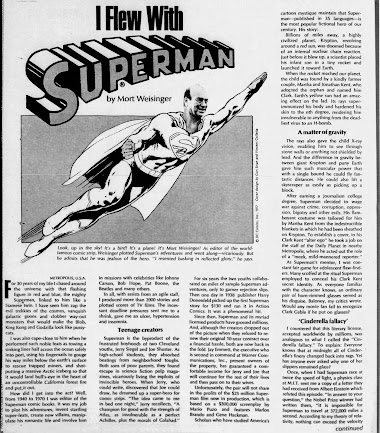

Graphic Novels in Bookstores--1988

I wrote this piece in 1988 but I'm not certain what for, exactly. At the time I was working at Waldenbooks but I wasn't associated with any company newsletters. I wasn't writing for fanzines and would still be a few years before I would even hear of something called the World Wide Web. It's possible I actually wrote this to try to sell to the local newspapers but there's no evidence the piece, written in pen. in cursive, in a notebook, ever left the house.

Here it is, below, only slightly edited from its original version. If you've been in any bookstore or Public Library in recent years, you know that the graphic novel sections are some of the most popular--and sometimes largest--sections! I was right!

Harold Robbins’ sexy potboilers could be described as “graphic” novels, but they are most definitely not actual graphic novels. A working definition of graphic novel might be a hardbound or a paperbound book featuring a story told by integration of words and pictures. It is also the next step in the evolutionary ladder of the lowly comic book.

Graphic novels have been possibly inspired by the widespread acceptance among adults of European and Japanese comics in more permanent album form. Although there were plenty of earlier attempts, the late 1970s brought the first efforts to market original graphic novels. Among the earliest were The Wizard King and A Contract with God. The Wizard King was written, drawn, and published by legendary comics artist Wallace Wood and was a lighthearted, sexy, version of a Tolkien-style quest. It was printed in two hardcover volumes in black-and-white. Wood’s untimely death in 1981 prevented the uncompleted third volume’s appearance.

At about that same time, another small publisher presented Sabre, an exquisitely drawn science fiction tale by Don MacGregor and Paul Gulacy with a philosophical bent. It was also black-and-white. Will Eisner, creator of the legendary Spirit strip in 1940, had been a vocal proponent of the graphic novel format for some time and in 1978 came out with A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, in sepia tones but in a more traditional book size. It dealt with a number of Jewish families in 1930s New York City. It had sex, but it wasn’t sexy; it had violence, but it wasn’t judgmental. It was truly an adult graphic novel. A child would've had little or no interest.

Eventually, Marvel Comics, then the kings of the comic industry, committed themselves to a graphic novel format for a regularly issued series of color books. After an impressive start with 1982’s The Death of Captain Marvel by Jim Starlin, most of the Marvel books that followed seemed like little more than overpriced versions of their regular series with only an occasional example worthy of the prestige format.

Their rivals at DC Comics took an even more tentative step starting with graphic novels based on classic science fiction stories by Bradbury, Bloch, Martin, etc. Then, DC stumbled onto a major variation on the format—repackaging Frank Miller’s revisionist history of Batman entitled The Dark Knight Returns, which originally ran as a four-book miniseries of comics. The entire story was repackaged as a phenomenally, successful, softcover and hardcover book.

Since Dickens, Conan Doyle, and many other classic authors had originally run their stories as magazine serials prior to collecting them in book form, this was not new. It was, however, new to comics. Currently Miller’s Ronin, previously a six-issue series, and Watchmen previously a 12-issue series by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, are both in release. Both titles tell a single cohesive story and both are prime examples of the modern graphic novel medium. Watchmen, especially, although optioned for a film, is perhaps the best use of the comics medium to date, integrating words, pictures, imagery, and analogy into the format in ways never seen before or since.

Meanwhile, legitimate book publishers were getting involved in the act. Donning Press repackaged Elfquest, an incredibly successful, black-and-white, independent comic, into four best-selling trade paperbacks. Donning has since gone on to produce several original graphic novels, as well as more repackaging of independent comics.

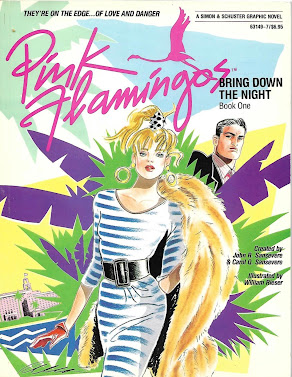

Several independent comics publishers have come out with their own graphic novels, including The Rocketeer from Eclipse Comics, Time2 from First, and Grendel from Comico. More recently, Simon & Schuster has released Pink Flamingos, a full color, graphic novel about a teenage girl rock group. Prominently labeled on the cover as a Simon & Schuster graphic novel, it isn’t very good, but it clearly shows that the company has liked what it has seen of the growing trend and was anxious to try the format. Other publishers are expected to follow suit.

Right now, most bookstores don’t know what to think of graphic novels. They usually throw them into the Science Fiction section or even Humor, despite their often down-to-earth, non-humorous content. It is not too far-fetched to say that bookstores may well have a dedicated graphic novel section before long.

Steven Thompson, 1988